In this two-part article, my aim is to take a look at diamonds and unravel some of the endemic confusion that exists around the politics of diamonds. I am always very aware that this is a deeply uncomfortable subject for most jewellers, who feel ill-equipped to deal with the consumer questions around conflict diamonds.

In this two-part article, my aim is to take a look at diamonds and unravel some of the endemic confusion that exists around the politics of diamonds. I am always very aware that this is a deeply uncomfortable subject for most jewellers, who feel ill-equipped to deal with the consumer questions around conflict diamonds.

The complexity of the problem is embedded in the international politics of the diamond trade, and the structural relationships between the principle parties; World Diamond Council (WDC), Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS), Civil Society Organisations and nation states, how they all interact to govern the flow of ‘rough diamonds’ and the differing expectations that all the parties have in regards to what the KPCS should be achieving. The WDC established in 2000 is the body responsible for overseeing and implementing the Inter-Governmental Process for the export and import of rough diamonds. The KPCS was established as the customs procedure to control the flow of rough diamonds from one state to another. Only states that were deemed free from conflict were given permission to export their diamonds.

The deficit that has contributed to the recent erosion of the credibility in the KPCS stems from the lack of agreement within the KPCS criteria regarding human rights issues and how this definition is outworked. The member countries cannot agree on human rights in general (i.e. China and America) never mind whether they should be included into what some consider to be a purely ‘customs procedure’. Can a diamond mined and exported from a country with systemic human rights violations be classified as a blood diamond? Some countries say yes, others say no. The case of Zimbabwean police and private security forces employed by State-owned mining companies in Marange,[1] arresting, beating, torturing and killing small-scale miners is a well-documented reality, yet these stones are called ‘conflict free’. Morality says they are conflict, the politics of money says they are not. This early mistake in the KPCS foundation created the ambiguity that has in turn been exploited by less principled actors in the diamond supply chain.

In truth, when the KPCS was established, the founders were dealing with a situation where diamonds were being used by rebel armies to over throw legitimate governments. They never envisaged a situation where an actual government would be perpetrating the human rights violations, as in the case of Zimbabwe. The recent imprisonment of Charles Taylor by The International Criminal Court in The Hague for his part in the diamond wars in Sierra Leone, reminds us that the conflict diamonds story is never far from the headlines.

In truth, when the KPCS was established, the founders were dealing with a situation where diamonds were being used by rebel armies to over throw legitimate governments. They never envisaged a situation where an actual government would be perpetrating the human rights violations, as in the case of Zimbabwe. The recent imprisonment of Charles Taylor by The International Criminal Court in The Hague for his part in the diamond wars in Sierra Leone, reminds us that the conflict diamonds story is never far from the headlines.

Equally the lack of a permanent secretariat has only compounded the inertia; as the WDC and KPCS have become a reactionary fire-fighting agency, rather than a pro-active weapon against corruption, human rights violations. They simply did not have the capacity to fulfil their principle mandate of protecting the diamond supply chain from blood diamonds.

In the global economy of diamonds, the disconnect between the source of our stones and the trigger to purchase for the consumer has inadvertently allowed this problem to develop as the market narrative is never about source issues, its is always about emotion and aspiration. And no one aspires to be a human rights abuser or wants to be seen to sanction it. This current disconnect, exposes the entire diamond supply chain to the chill winds of devaluation through negative human rights stories. The current inertia within the WDC and KPCS, and the destructive arguments between the consuming countries (western) and the source and manufacturing countries (Africa, India, China) is an exercise in abstract futility, when viewed through the lens of market forces.

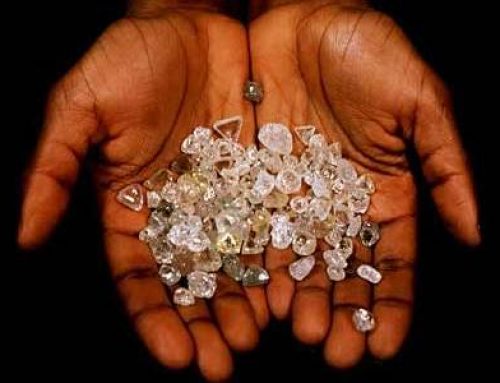

The hard facts demonstrate that you cannot divorce source from end consumer. They all work on the same economic continuum. 200 million carats are mined every year, of which 50% goes industrial at $3 per carat, the rest to gem at an average of $50 a carat. In fact the true measure is that 90% of the global value of diamonds is carried in less than 10% of the production, all of which is gem value and exclusively brought by consumers.[2] This short exercise in numbers proves the mining and manufacturing countries are dependent on the consumer perception of the diamond as a worthwhile and untainted product. It is incumbent upon the WDC to impress upon its members that if the diamonds lose their inherent value through negative human rights stories, they will have no business.

The vulnerability of the diamond to negative messages is enshrined in the veracity of its economic structure. In my opinion the historic diamond brand narrative that ‘A diamond is a girls best friend’ and ‘ A diamond is forever’ is no longer strong enough to maintain the mirage that everything is rosy in the diamond garden.

In my second article I will examine the positive words emerging from the recent WDC KPCS meeting in Vicenza and ask ‘Is the Kimberley process going to rediscover its ‘mojo’, or continue to play politics with the future of our industry?

Diamond-funded human rights violations are not confined to the trade in rough diamonds – cut and polished blood diamonds evade the strictures of the Kimberley Process and flood the market. But because Israel is the main source of cut and polished blood diamonds no one in the diamond industry is prepared to speak out.

The most glaring example of cut and polished a blood diamond must be the De Beers Forevermark Steinmetz Jubilee Diamond on display in the Tower of London. This diamond was cut and polished by Steinmetz – a company that funded and supported the notorious Givati Brigade of the Israeli military during the assault on Gaza in 2009/9009 when over 1,400 people, including more that 300 children were killed. The massacre of 21 members of the Sammoni family by the Givati Brigade in one incident was probably the most serious example of gross human rights violations recorded during the three week assault against the besieged residents of Gaza. Do the human rights of Palestinians not mater to the diamond industry? http://www.ipsc.ie/press-releases/gaza-family-victims-of-israeli-war-crimes-appeal-to-british-queen-to-remove-blood-diamond

The Kimberly Process is deeply flawed especially with regard to Israeli blood diamonds. It means that no-one of conscience can buy diamonds as they could well be funding apartheid, occupation and warcrimes committed by Israel against the Palestinian people. This anomaly in the Process renders it null and void as a safety net to prevent blood diamonds from contaminating the market. Israel is a state in breach of so many international laws, profiting from and using blood diamonds to fund their human rights abuses, Israeli blood diamonds should be marked so people can know not to buy them.

It has been estimated that diamonds are a major source of funding (Approx. $1 billion annually) for Israel, and hence its military and so-called defence forces ~ those which maintain the occupation, which does little to “defend” Israel, rather is a major source of irritation and instability, which miraculously does not lead to nearly as much violence as one might expect, due to the amazing “sumud” or peaceful steadfastness of the Palestinians.

Please check this out ~ and blog about the injustice that Israeli diamonds, and diamond exporters are supporting ~ even the Queeen has been drawn into this by allowing the De Beers Forevermark Steinmetz Jubilee Diamond to be on display in the Tower of London.