Over the next three posts I will be reflecting from my journals on my trip to the Democratic Republic of Congo, where I had been invited by Peace Direct to explore a grass roots idea of using small-scale gold mining as a means of building a peace and reconciliation process. A bold plan in the face of the well recorded troubles.

Anyone who travels in Africa must be blessed with patience and an unswerving belief in the inherent goodness of humanity, not something I believe St Augustine (an African himself) the inventor of the doctrine of original sin had in abundance when he came up with that innately negative outlook. This belief was tested upon my arrival at Entebbe Airport where I was transiting to Bunia in the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. The immigration officer retains my passport and allows me the freedom of this singularly underwhelming airport. I then wait for four hours for what is increasingly looking like a mythical representative of the small airline company who will be flying me to Bunia to issue me with my pre-paid ticket. As I sit in almost solitude I have re-occurring visions of scenes of torture and abuse from the film The Last King of Scotland, grateful those days have long disappeared from Uganda. Eventually a lady arrives from the airline company and asks for my passport. For ten heart-stopping minutes the half-dozen immigration officials, who are all busy chatting, half-heartedly move piles of envelopes and papers from one side of their desks to the other, whilst telling me ‘I need to relax’. In this matter of humanities inherent goodness, I am vindicated as my passport turns up from another room, only to disappear again with the airline lady to be shown to another mythological person in an upstairs room.

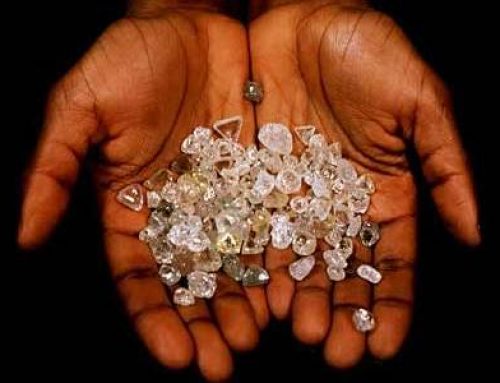

After another two hours the small twin prop flight to Bunia dances through the clouds and over a scattering of lakes, rocky hills, bush and forest that keeps my aching body entertained. Bush fire smoke drifts across the landscape telling us the wind direction and that the land beneath is inhabited by, if you believe the popular media myths of the west, bandits, militia and smugglers of conflict gold. A narrative I have been guilty of perpetuating in my career as an ethical jeweller and not without a measure of truth attached to it.

Arriving at the Bunia airstrip is a small education in the challenges the DRC faces on a daily basis. After my passport is stamped with a date stamp similar to the ones you can buy in any stationary store, I collect my bag from the nose of the plane and take it to a room full of cardboard boxes and plastic chairs to be inspected by a customs official in a garish blue and yellow shell suit. As he opens my bag he spots my camera and removes it from its box and in an animated French Swahili diatribe, announces this is not permitted in the country. He declares it is a telescopic camera that can link to the Internet via a satellite and can also be used to film the local underwater wildlife which last appeared in this region during the Jurassic period. Others begin to emerge from small rooms off the main cardboard room and join in what rapidly conflates to a game of pass the parcel amongst eight grown men. Eventually the camera, in the mass confusion disappears into a back room and I am told through Henri Ladyi, the co-ordinator of The Centre for Resolution Conflicts (CRC) that they want a $100 tax to import the camera. I refuse to pay.

As I am clearly no longer part of the discussion I decide to adopt a stance of calm self-preservation, as I recognise I am going to be here for a long time. I sit down, open my Bible and go into a state of Zen-Christian exhaustive Lectio-Divina. Eventually the commotion attracts the attention of the airport police and the situation becomes further magnified when the location of the camera cannot be determined. What had started as an attempt to bribe a visitor has now become a case of theft. Some one has stolen my camera. The volume increases again to a pitch that would rival Jimi Hendrix’s rendition of Wild Thing at The isle of Wight Festival in 1969, as the airport customs boss now realises that he has an incident on his hands that involves the Police. With the head of Airport Police involved the noise hits a new and more frenzied level. The original customs officer in the garish blue suit, has been found to have stashed the camera in his bag. He makes a statement to the Police and after much ‘tooing and froing’ between officials in the airport the offender turns out to have been drinking on the job and is now pleading to keep his job and not be charged by the Police. The noise has by this stage reached the District Head of Customs who has driven down to the airport to take personal control of what seems to have become a diplomatic incident. At the end of three hours, two police statements later and a very contrite and worried corrupt customs official I am given back my camera by the District Customs Officer in a ceremony that includes a photo shoot, a very formal verbal apology and a letter I have to sign, all during a long handshake. There is nothing low key about my arrival.

Meeting Henri and hearing his story is both inspiring as will as very distressing. Distressing because he like so many in this war torn country he has suffered. Having lost his father to a rebel attack, he joined a local militia in order to protect his family from other similar events. Inspirational because his wife persuaded him to turn from being militia to becoming a peacemaker when she threatened to pack up and leave for her parents. The insecurity of living with violence was too much for her to cope with, especially with a young family. In 2003 he and his family found themselves in the Mukulia IDP camp as they fled the ethnic violence that had erupted at the time. Whilst in the camp he started to work across the ethnic divides and to build a local peace movement by facilitating dialogue, interaction and mutual understanding between historic rival groups.

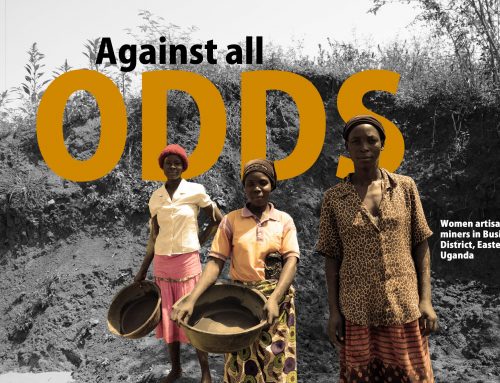

I am to be based in Bunia for the week, one of the main towns in the Ituri district of Oriental Province. Bunia is the home to the recently re-opened United Nations MONUSCO mission. Re-opened, as a few months ago it was attacked by students from the next-door University as an outpouring of anger and frustration at the unsettling and accidental death of a student at the hands of the UN, which forced the UN to move out of Bunia for a short period of time. My first job is to register at the UN and to receive a security briefing. The guards seem slightly confused as I ask them where to go to register myself for security purposes, but eventually, after visiting three separate offices I am introduced to a man, who points to a map and informs me that the road is ‘green all the way to Aru in the north, anywhere south of Bogoro you will need a military escort and do not head west, (he points to a huge space on the map that is effectively empty), as it is full of poachers and militia’. I am instructed to keep my satellite phone with me at all times and stay in radio contact. I am told as I leave that the current security situation is ‘Calm but Volatile’. I confess to being slightly nervous now as I do not have a satellite phone and I am rather reliant on a mobile phone signal and the wisdom of Henri and team who know how to navigate this region with aplomb. Next we visit the Congolese security service office, where after a hour of French chit chat, we are issued our travel stamp on the requisite document, I am given a lecture by the Chief of Security in why I should not be doing this, and we are sent on our way. My next stop is one of the artisanal mining sites that is part of the peace building process.

Well, that was entertaining 🙂

You certainly have been on an adventure. Can’t wait for Part II !

Great work Greg. Started my own blog on the ruby mine and orphanage http://www.rubyfair.com/blog/ Tending to find attitudes changing so keep going !