An Interview with Mike Koostachin by Marc Choyt

Introduction/Situation Briefing

In December, 2009, members of the Attawapiskat First Nation, part of the larger Cree First Nation group, staged a major blockading at the De Beers’ Victor Mine in northern Ontario. Mike Koostachin, was the first person there. He considers himself a keeper of traditional ways, and works as a cultural liaison in the schools, teaching Cree values to children.

Mike and I first talked about the situation at the Victor mine after the initial blockade, in February, 2010. In researching this article, I obtained documents from De Beers First Nation employees written to management that confirmed Mike’s concerns and raised other issues relating to how spills are cleaned up, the treatment of First Nation people at the mine and a rape. The documents also showed a willingness on the part of De Beer’s personnel to address these issues.

The Victor mine is located in such a complex and difficult cultural and environmental context. Any alliance between members of the Attawapiskat Nation and De Beers would inevitably be fragile. The village is poor and in great need of jobs. Many feel hopeless—watch this Canadian News feature and you’ll see why the suicide rate is so high. An article on Attawapiskat in Canadian Geographic reveals the struggles to get a new elementary school to replace its current one which is highly toxic. Not only is there benzene in the aquifers, but sewerage commonly floods into their drinking water.

To gain the trust of the Attawapiskat, De Beers worked hard to employ a community sensitive approach in its negotiations, The village desperately wanted economic development. De Beers is obviously not a development or relief agency: they are there to make as much profit as possible. It’s likely, however, that this level of engagement—over 100 community meetings, created high expectations. I contacted Tom Ormsby, De Beers External Relations to get De Beer’s perspective on the current events, but he did not return my call.

For the some traditional Attawapiskat, the deal with De Beers has not been worth it and they are bitter about the entire situation. They believe that, except for a few individuals, the positive economic impact on the village has been negligible. Meanwhile, the land, animals are highly impacted and the fish have elevated levels of mercury.

The impact of the mine is clearly a threat to what perhaps many Cree would consider their greatest wealth — a traditional way of life intimately linked to their place on earth. As cultures and world views have clashed, communication on many levels has broken down. The result has been two blockades fueled by the anger and betrayal many Cree feel toward De Beers.

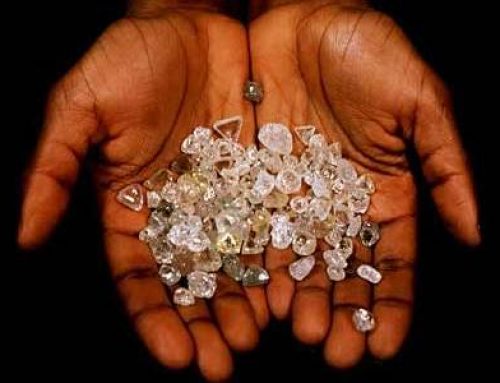

“They are the same regime, a modern day regime. They have our tribal government. Instead of cutting off your arms and feet like they did in Africa, they are cutting off our land, our food from the land. The people are the land.” Mike Koostachin

Marc Choyt, Fair Jewelry Action, USA.

First, I would like to start out with the question, where are you from?

I’m from Attawapiskat. It is a fly in community, very isolated. Cree Tribal Group. My village is about 90 kms from the De Beers diamond mine.

Do you speak for anyone in an official capacity as a tribal official?

I basically a member of the Cree First Nation, concerned about the development in the area. I am an Aboriginal Liaison Youth Worker and my work is to teach cultural knowledge to the First Nation student. I’m deeply committed to the values of my people. When I look at the development, I think about it in context to my culture and my connection to the land.

What happened back in December, 2009?

We decided to form a blockade to prevent access to De Beers’ Victor mine. I was the first one. Within minutes of starting the blockage, there were over 50 people. This was in February, 2009.

We went on the winter road, across the river, and there was a lay down for transfer of equipment, where you go park yourself, like a transport. We set up a barricade, a construction barricade, like rail road ties, like a tripod.

Then, within hours, trucks came by, their first haul. They had stuff that had to go in and out of the diamond site. There was another convoy coming in from the south from Mousley. They turned around. The other ones coming from the Victor site, the blockage, came within less than 100 meters of the blockage—3 trailers. They went back to their origin with their escort.

How did the De Beers respond?

About midnight, John White, a liaison for De Beers—he passed away that winter, came up to the blockaders He asked who was the leader and who to talk to so that he could take his concerns to his management. We told him, there is no leader. So we stayed there.

How long did it last?

The blockade lasted 18 days—we hired a lawyer. First Nation and De Beers agreed to pay the lawyers. We have outstanding legal fees of over $100,000 and our lawyer is not getting paid. To stop the blockade we signed a good faith agreement. People who worked on the site were concerned about losing their jobs—we were split up.

Employees from mine site came to the meeting. We thought that they would get pissed off at us and give us shit. But they supported us.

What were the issues of concern?

It had to do initially with our Impact Benefit Agreement (IBA), which is the money the tribe gets for giving up the land, for the mine. During the summer of 2008, there was a petition going around in the community. I was one of the people that walked around with the petition, to revisit the IBA agreement. It was proposed by our tribal government, but never ratified by the people.

(Note: Here’s a link to an article that details the issues in contention in that first blockade.)

How was the original IBA agreed upon?

It was voted on, as a referendum. People wanted the mining to go ahead. About 270 said yes, and 80 to 90 that said no.

People that said, yes, thought that they would get money from the project, in their hands. They were promised 2 million a year—a million up front for signing the agreement and 2 million a year for the life time of the mine. Basically, it would be 30 million over the course of the mine to 1800 to 2000 community members. Less than 20% voted, but De Beers said it was 90%.

Why didn’t more people vote?

People were not really into the process of it—there was a lack of understanding.

Then, during the referendum, the community had a signing agreement ceremony. Now, we have nothing from the IBA and no employment opportunities.

Have members of the tribe, the larger community, get the money?

No. There has been no money. The leadership established a trust fund for the community. Though the funds are there, but there is no accountability, no reports from the tribal leadership report to the shareholders.

Still don’t know what the IBA money is doing?

No.

But De Beers can’t be blamed for that.

It is the First Nation’s leader’s fault. They have funds coming into first nation – no transparency, to this day.

What has changed since the mine was opened?

Nothing. They generally offer First Nation people low positions, like sweeping the floor, doing dishes. No employment and training services.

What kind of agreements with other communities?

Jobs, trust fund, same thing. IBA—but some of them have their own stipulations to protect their culture and traditions. We compete with them, even though the mining impacts our community primarily.

People say that Canadian diamonds are conflict free.

At the beginning, there was not a lot of conflict. People did their consultation. Once the mine was at the exploration stage, they had to do a test for kimberlite. People were not yet opposed to the impact of the mine. A lot of people did not think that the mine would go ahead. They did not think about the destroying of the land, to have a big hole. They didn’t think they would find anything. But now, people are worried.

Why?

When they live off the land, they see fish being deformed. The water tastes different. There was disturbance of our caribou that migrate through the area—we don’t see them anymore. Moose reduced as well. This happened last summer. The caribou herds are in decline and the animals are no longer close to the villages due to the impact.

Also, we are seeing high levels of mercury in our water. We are seeing deformed fish.

But diamond mines don’t use mercury.

The mining is in the swamp and the moss acts like a filtration system for heavy metals when the rain falls and goes into the river. The moss is being picked up and the swamp is drained and bypassed over to the river.

The mercury was in the moss. The moss was removed in the strip mines, resulting in heavy mercury contamination in our rivers. A million tons of water of day, floating from the swamp to the river. So mercury is leaching into the river.

(Note: See this report which documents the elevated levels of mercury in the Attawapiskat river: “There is not safe amount of consumption of northern pike… for women of child bearing age and children less than 15 years of age.”)

Yet people say that the mines in Canada are well regulated and run. There is this cherished belief among jewelers, particularly the ethical jewelers, who rely upon Canadian diamonds.

We don’t believe that the mines are ethical. The letter I wrote to Canadian Mining Watch —no one even responded to it. Ministry of Natural Resources of Canada and Ontario and Oceans and Waters and Fisheries.

Right now, De Beers imports petrol on winter roads. Eight million litres annually. When they transport the fuel from Moosonee, Ontario to the site, it is 350 km to transport fuel. Four or five tankers going by daily. The diesel spills are of great concern. One of the concerns also is the addition territory where people occupied the land. Then there is the issue of power lines constructed to the mine and the land being disturbed.

I’ve been reviewing internal documents sent to me, specifically, from a First Nation De Beers employee at Victor Mine this past December. He raised a number of issues, including, non-native people getting the special treatment and complaints about the present camp administrator. He seemed frustrated that these issues have not been address. Your thoughts?

There is nepotism on site for non-First Nation members.

What about the issue on spills on site. I read in one of the internal documents that First Nation employees are more concerned than non-Native employees. What evidence do you have for that?

The spill is covered up right away and safety officers will cover this up because they don’t want any trouble from ministry of environment with Ontario government.

To what degree has De Beers hired local people?

In the construction phase, there were 800 people hired. Now it is in operation—less than 400 people on site; 100 people are aboriginal people who work there. The signing was that the people in our community would get the first crack at the jobs—that hasn’t happened. But the criteria was grade 12 and 5 years of experience mining. Couldn’t hire from our community because not enough people could meet the criteria.

Also, when De Beers came in, De Beers signed agreements with other first nation groups—so we are competing with jobs with them. It was a divide and conquer approach. But the mine is located in our traditional area. They employ about 100 First Nation people, but of those only 40 are from our communities. Of those, perhaps about five are upper level positions that required training.

What led to the current blockade that is taking place?

The people were told they would be given opportunities, such as jobs, using machinery on site for the construction of operations on the mines and for exploration projects. These jobs never came through—they were handled internally by De Beers’ so there have been no opportunities for small contractors.

When did it start and how many people are there at the blockade?

It started February 11th at 2:30 PM EST. Twenty people, plus the people who support them in the village.

(Note: here’s an article that gives De Beer’s and Tribal officials view of these events)

Are they there day and night? What are the temperatures?

24 hours and the temp. is -41 Celsius plus the wind chill

How effective is the current blockade?

The chief of the village wants it open. But there is political corruption in the community.

In the last blockade there was a mediator, but the mediator worked for De Beers. They paid this person. That mediator was so much controlled by the former chief who was close to De Beers. So what happened was the mediator uncovered unethical practices from the former chief from handling affairs. She was on the chief side.

There’s massive corruption in our tribal government which is managed by what in Canada we call the “Band Office.” It is a third party office to control our finances. Right now, we are in a 14 million dollars deficit. How can we be in deficit when we have a diamond mine in our back yard?

How was the money lost?

It is corruption that is happening at local level and there’s split between the government and the people. There was always a split in terms the mine coming—whether or not it should be there. Now, the government is getting royalties and mismanaging the fiscal responsibilities of the tribe.

Our land is contaminated. Our water is contaminated. Our First Nation government is corrupt with a 14 million dollar deficit and they are saying it is the fault of the people, and we have a diamond mine next door.

Do you have much confidence in DeBeers?

They are the same regime, a modern day regime. They have our tribal government. Instead of cutting off your arms and feet like they did in Africa, they are cutting off our land, our food from the land. The people are the land.

[…] forever” but a diamond mine is not. The one near Attawapiskat will last 11 years; then the jobs (few and mostly menial) and the project funding are gone. Still, credit where credit’s due – De Beers did not start […]

Where do you start? How do you educate the so called educated in the ways of the land? Sadly you live in a prison. Who was it that said they have no bread give them cake to eat? I am saddened to see a fellow being treated this way. Canada is becoming more and more a third world country!